Softbot Design with WANNS

Introduction

I’m a Brazilian undergraduate student in Computer Science and I spent the past 3 months in the University of Tsukuba doing a research internship under Professor Claus Aranha. Here I will talk about my project during these past months to the best of my memory and in the end write down some lessons learned.

The research idea

Softbot Design

Soft robots (softbots) are robots built from highly compliant materials, similar to those found in living organisms1. There are many interesting applications for robots made from biological materials, like delivering drugs to specific parts of the human body and general interaction with the insides of a human.

The paper Unshackling Evolution models the design of softbots as filling a cube with voxels in 3d, each voxel being of 4 possible types:

- Muscle 1, an active and soft material that actuates periodically, represented by green voxels

- Muscle 2, same as muscle 1, but when muscle 1 expands muscle 2 contracts and vice versa, represented by red voxels

- Bone, a passive and rigid material, represented by dark blue voxels

- Skin or flesh, a passive and soft material, represented by light blue voxels

And then simulating the resulting robot using a physics simulation library called voxelyze. The aim of the task is generating softbots that walk the farthest in a given timescale and the paper compares the design of the softbots using direct encoding versus generative encoding (CPPNs)

CPPNs

Compositional Pattern Producing Networks are one of the coolest ideas I’ve seen in Machine Learning, combining the flexibility of Neural Networks and the ability of Genetic Algorithms to optimize functions with hostile optimization landscapes to generate pretty much anything.

Now for the more technical details, CPPNs are used to generate patterns in a manner similar to a printer head, where they walk through each point in space and associate an output to it. To exemplify that, if we want to generate an image a CPPN will receive the x and y coordinates of each pixel and as output generate the color of that specific pixel. You can also pass some additional information in the input, for example distance from the origin or from the center, or if you’re building 3D structures you could pass distance from the axes.

But how do we model the function associating points in space to colors? That’s where the Neural Network comes in, as NNs are universal function approximators and so we could in theory capture any pattern we want, given a sufficiently big net.

Finally we have that CPPNs tend to not have a fixed architecture and use many different activation functions in each of its neurons, so we use a neuroevolution algorithm, like NEAT to evolve a neural network that produces the pattern that we want.

Weight Agnostic Neural Networks

While classically CPPNs are evolved by using NEAT my research was initially concerned with what kind of CPPNs would be evolved by using David Ha’s weight agnostic neural networks.

The aim of WANNs is evolving a neural network architecture that encodes the solution to the problem, de-emphasizing the weights of the connection between neurons. To that end we generate a population of randomly wired nets and evolve them by randomly adding new nodes, new connections between nodes and changing a node activation function, and testing the network with a few (generally 6) random shared weights, and setting the fitness of the individual as the average fitness from the net using the random weights.

WANNs show surprisingly good performance while using a single shared weight across all solutions compared to a normal fixed architecture with the same constraint of using a single weight, but they only achieve performance comparable to state of the art by training the weights of the final architecture, as you would with a normal NN.

Reading the codes and creating the environment

Getting the codebases and translating to modern python

My first challenge with this research was setting up my environment, as I had to initially combine David Ha’s Weight Agnostic Neural Networks code with the Unshackling evolution challenge. Thankfully I found Kriegman’s github, where he implemented Unshackling Evolution in python, calling it evosoro (for evolution of soft robots), though it was still in python 2.7 and so I would need to do some translating to python 3 before merging the codebases.

A few dozens of unicode errors later and evosoro was up and running in python 3.6 and so I could start thinking about merging the codebases.

Merging the codebases

Both projects were somewhat extensive, evosoro especially as it was written in a very general way as to make it easier to implement other papers beyond Unshackling Evolution. After a good deal of time reading through the code I decided to use David Ha’s code for optimization and create a Gym Task based on Voxelyze.

Initial experiments

Initially the experiments showed little progress, with the softbots generated after 100s generations being barely capable of moving at all, and being extremely below the expected fitness, which was quite worrisome.

I spoke to Claus and he advised me to check the output of my models instead of just looking at the metrics as that would help me better understand what my model was learning and what exactly was the bug.

Quality Diversity Detour

Since I believed I “just” needed to fix a few bugs I decided I could already study some techniques to explore the design of softbots, so Claus suggested I studied Quality Diversity algorithms and try to implement them on the project. I read Quality and Diversity Optimization: A Unifying Modular Framework and Quality Diversity Through Surprise, learning about extremely interesting techniques, like MAP-Elites and Novelty Search with Local Competition, that aim to increase the diversity of solutions found by evolutionary algorithms, while still maintaining high fitness, in fact getting higher fitness than algorithms focused on quality alone.

After around one week of studying I presented what I learned to the procedural generation group and went back to focusing on debugging the code, instead of adding functionality to a buggy codebase.

Lack of results and some despair

After looking at the specific output of my networks I found a bug I had introduced when creating the evosoro environment that caused my algorithm to never generate one of the materials and to consider “empty” as a possible material even after the first check, that helped the program generate less sparse softbots and increased the performance, but it was still quite low. Besides that voxelyze took quite a while to run and since each WANN needs to be tested 6 times that meant that experiments would take an entire day running only for me to be met with low performance, since I had to generate some kind of report to my funding agency in the end of the program I stopped working on the softbot design for a while and simply do something that wasn’t done in the original WANN paper despite being relevant, comparing WANN Search with its parent method, NEAT.

Comparing WANNs and NEAT

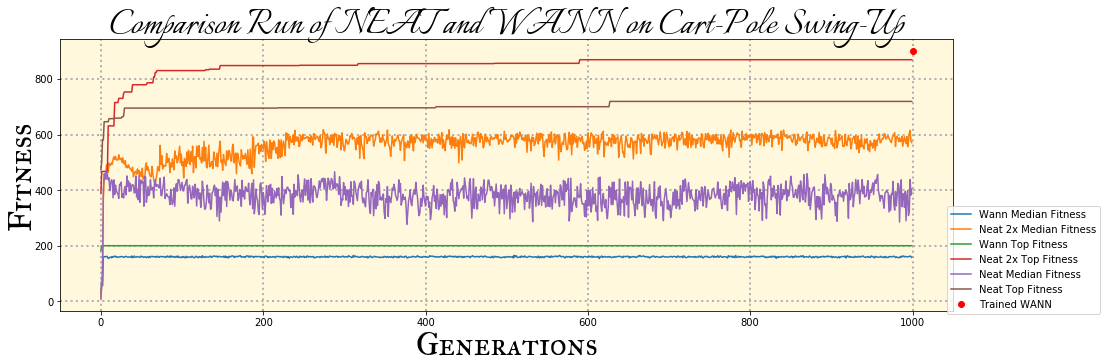

To that end I compared NEAT and WANN with the same hyperparameters in the cartpole swing up task. The main takeaways were that NEAT trained faster, requiring considerably less compute to reach good performance, but while WANN’s connection could be trained to reach 3x the networks initial performance, NEAT would only gain around 10% extra performance. That wasn’t particularly surprising, as NEAT is optimizing the weights during evolution, while WANNs are using a fixed shared weight.

Bug found!

I thought about Claus advice of visualizing the output of my algorithm again, and realized that the output wasn’t just the softbots, but also the CPPNs architectures, so I worked on visualizing the networks generated. There was a directory called vis on the WANNs repo on github, so I used it, at first there were a few incompatibilities that I had to fix, but soon enough a very weird error was being reported: the activation functions of many nodes were not in the correct range (from 1 to 10). That was counter intuitive, I took a look at the code and didn’t seem to find any specific mistake on it, so I added a quick debug print that would tell me should any activation outside the correct range be generated. After a few extra experiments I realized there was a bug on Google’s code! Specifically they have a function that used the + operator as a way to merge lists, but when the function was called one argument was a list, while the other was a numpy array, and so the behavior of the + operator was rather different, summing the content of the lists instead of concatenating them. I fixed the bug and sent a Pull Request to their github repo, that Adam Gaier accepted.

Evolving Neural Nets post bug

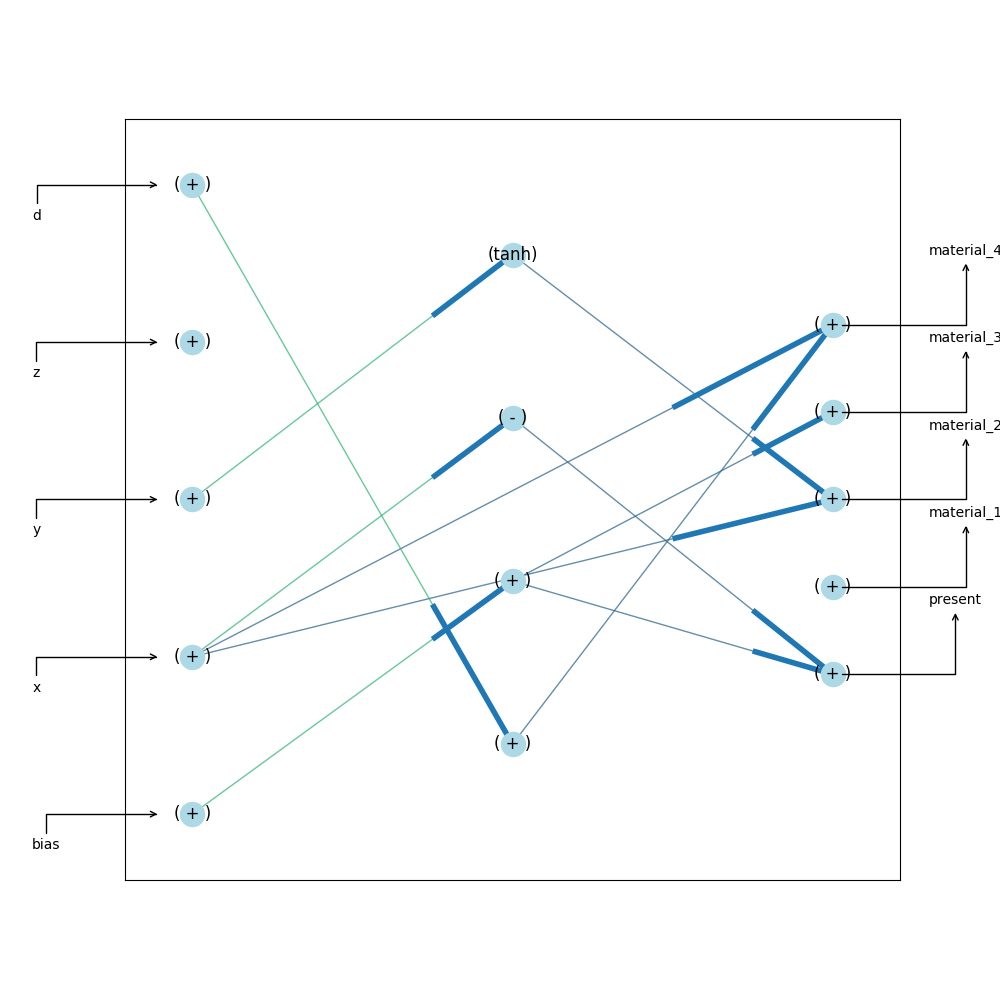

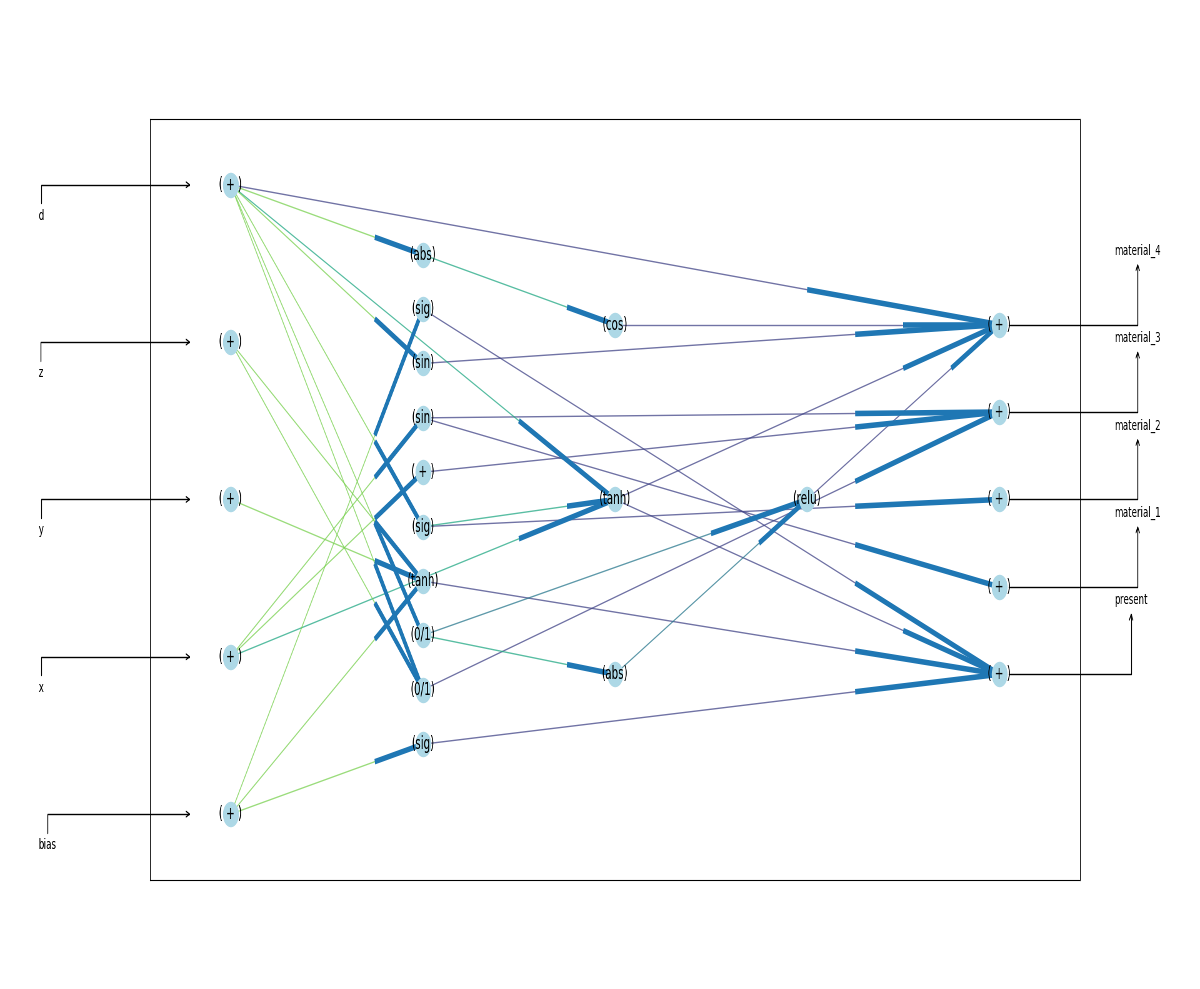

After fixing the bug the performance improved again and now it was finally possible to generate Neural Networks with many different kinds of activation functions. Here’s an example of a net before the bug:

And one after:

Different inputs and results

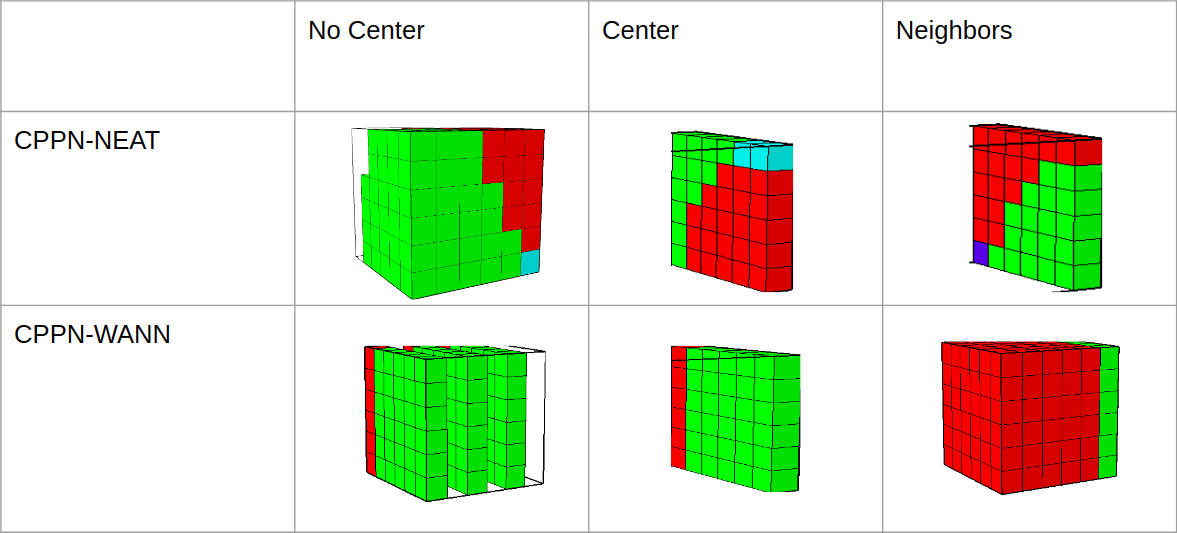

Finally I am now studying the use of different inputs to my CPPN, besides the x, y and z coordinates and distance from center. As of now I have tested not passing the center and also tested passing the material that was used in the voxels neighbors. Here are some preliminary results, both using 30 generations with a population of 60 individuals and the WANNs being untrained, just evolved:

|-| No Center | Center | Neighbors| | NEAT-CPPN | 15.94 | 20.17 | 21.31 | | WANN-CPPN | 18.66 | 19.22 | 13.83 |

I still need to run these experiments for more generations as that will probably allow for a bigger performance difference to arise, and run them a few more times to get averages to account for bad and good random seeds affecting the results.

There were some extra challenges related to dealing with weights optimization using CMA-ES and using PEPG, but this post is quite too long as it is, so maybe I will talk about that in the future.

TL;DR: Lessons Learned

- Always check your model’s outputs, metrics are a good way to diagnose simple problems, but looking at the output can give you qualitatively better understanding of any problem you come across

- Don’t assume anyone’s code is bug free, especially your own

- Iterate fast, especially in the beginning as that will help you fix any initial bugs and start doing real experiments sooner. This can mean using a small subset of your data, use smaller or simpler models that still represent your idea or using smaller populations and less generations in a genetic algorithm

- There is a sweet spot between pivoting too much and spending too much time in a doomed project, everyone is in some point in that spectrum, try to discover if you abandon things too quickly for newer shinier ideas or if you stay too long with an idea that won’t ever work

- Talk to your adviser. Just do it. If you have a progress to show, great! If you’re somehow stuck explain why to them and they will probably manage to help.

- If your adviser is not helping you it may be a good moment to try to find another one or have a serious conversation with them

- Write from the beginning, I didn’t write what I was doing before and recollecting everything took about an entire day. If you keep a log of your experiments, results and ideas it’s easier to spot faulty assumptions, brain farts and similar mistakes, besides helping you remember all the experiments you wanted to run

- Write a makefile, in the beginning it may only have a run and a git update recipe, but as you go along and start using doing different kinds of experiments makefiles will help you not make a typo when writing what command you want to run

- Have fun and don’t be too hard on yourself